In 1851 the journalist, playwright and liberal philanthropist, Henry Mayhew, published the first edition of his masterpiece, 'London Labour and the London Poor'. Like most liberal philanthropists Mayhew had been slumming it with the wretched denizens of Victorian London in order to write a book about their pitiful, penurious existence. The resultant work is littered with harrowing accounts of deprivation. There is a chapter, for instance, entitled, ‘The Afflicted Crossing-sweepers’; followed by, ‘The most severely afflicted of all the Crossing-sweepers’; which in turn is followed by, ‘The Negro Crossing-sweeper, who had lost both his legs’. Since he was an exact contemporary of Dickens it seems inappropriate to use the adjective ‘Dickensian’ here - particularly as the latter relied on this book for much of his background material - but you get the idea. We might say that Dickens was in fact ‘Mayhewian’ - if only Henry had written popular serialised novels instead of huge overly-meticulous sociological tracts.

In 1851 the journalist, playwright and liberal philanthropist, Henry Mayhew, published the first edition of his masterpiece, 'London Labour and the London Poor'. Like most liberal philanthropists Mayhew had been slumming it with the wretched denizens of Victorian London in order to write a book about their pitiful, penurious existence. The resultant work is littered with harrowing accounts of deprivation. There is a chapter, for instance, entitled, ‘The Afflicted Crossing-sweepers’; followed by, ‘The most severely afflicted of all the Crossing-sweepers’; which in turn is followed by, ‘The Negro Crossing-sweeper, who had lost both his legs’. Since he was an exact contemporary of Dickens it seems inappropriate to use the adjective ‘Dickensian’ here - particularly as the latter relied on this book for much of his background material - but you get the idea. We might say that Dickens was in fact ‘Mayhewian’ - if only Henry had written popular serialised novels instead of huge overly-meticulous sociological tracts.

Despite this the work contains fascinating glimpses of the variety of life upon the squalid streets of mid-19th century London. It is full of informed social observation, in-depth character portraits, and detailed statistical calculations concerning the price of horse shit. Here are some edited highlights.

When ‘dog-fancying’ (modern translation: owning a dog) became popular with the affluent classes, it didn’t take long for ‘lurking’ (modern translation: hanging about on the street until you see someone walking their dog, then nicking it), to become popular with the concomitant thieving classes. Lurkers were known to operate in two-man teams: one would lure the dog away with a slab of liver, whilst the other confused the beleaguered gent by pointing in a different direction and saying “they went that way”. The lurkers would then sell the dogs to hawkers who would sell them on again to other unsuspecting aristocrats.

When ‘dog-fancying’ (modern translation: owning a dog) became popular with the affluent classes, it didn’t take long for ‘lurking’ (modern translation: hanging about on the street until you see someone walking their dog, then nicking it), to become popular with the concomitant thieving classes. Lurkers were known to operate in two-man teams: one would lure the dog away with a slab of liver, whilst the other confused the beleaguered gent by pointing in a different direction and saying “they went that way”. The lurkers would then sell the dogs to hawkers who would sell them on again to other unsuspecting aristocrats.

It was common for a reward to be offered for the retrieval of stolen dogs, and thus another employment opportunity arose for sly scoundrels looking to make a quick shilling, i.e. as a 'dog-finder'. Unbeknown to the dog-fanciers, however, the dog-sellers and the dog-finders were generally the same people, and more often than not they stole dogs solely to collect the reward. If no reward was offered they either threatened to torture the dog, or just killed it and nicked another one.

As dogs were not legally considered ‘property’, the lurkers were undeterred by the prospect of being imprisoned, let alone getting caught. In one instance, when a lurker did get sentenced, he was charged not for stealing the dog, but the collar. The owners were nevertheless in the absurd position of having to pay a dog-tax, which also meant they often ended up having to pay for a full term even though their dog was missing/dead/being tortured. In addition, if a high reward was readily paid then the same dog would invariably get filched again. Mayhew reports that a certain Miss Brown of Bolton-street was so fed up of having her dog repeatedly stolen that she left the country.

This was also an age, remember, when the recycling of natural resources was an imperative of poverty rather than a hobby for the conscientious. Hence the streets were scoured by hordes of eager invalids, old women and disgraced rag-gatherers on the look-out for any unclaimed turds to shovel into bags and sell to tan-yards for half a pittance. Except, of course, only a few of them could afford shovels. Most had to use their bare hands.

That the term ‘pure’ actually referred to ‘shit’ is not due to some ironic cockney colloquialism, but because it was thought to have "cleansing and purifying properties". Apparently in the tanneries it was customary for prospective purchasers to use "both nose and tongue" to judge whether the leather had been purified (i.e. had shit rubbed into it). If the leather was not treated properly (i.e. not had shit rubbed into it), it retained moisture and started to smell. Presumably the Victorians found the odour of damp hide especially offensive. Mayhew is not altogether clear whether dog shit was thought to possess these cleansing properties specifically in relation to leather, or in general - perhaps as an affordable alternative to soap. Either way the tan-yards were quite particular about the types of defecation they accepted: some preferred the "dry limy-looking sort" whereas others valued only the "dark moist quality". Often, when selling their wares to the tanners, the more enterprising ‘pure-finders’ would mix different varieties of dung to supply the demand.

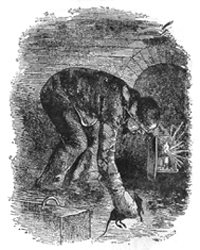

If one were in the habit, in that day and age, of spending an idle afternoon beside the Thames, one may have observed a number of degenerates, known as ‘mud-larks’, wading through a substance known as ‘mud’, in search of worthless artefacts. There was, however, a more intrepid species of degenerate known as ‘Toshers’, who would venture even further into the rancid filth of the city’s underbelly in search of worthless artefacts. Yet, if one could afford the luxury of an idle afternoon in that day and age, then one would have been bourgeois and would have immediately alerted the local constabulary - for the Tosher’s domain was none other than the city sewers themselves, and entering them was as illegal as it was dangerous.

If one were in the habit, in that day and age, of spending an idle afternoon beside the Thames, one may have observed a number of degenerates, known as ‘mud-larks’, wading through a substance known as ‘mud’, in search of worthless artefacts. There was, however, a more intrepid species of degenerate known as ‘Toshers’, who would venture even further into the rancid filth of the city’s underbelly in search of worthless artefacts. Yet, if one could afford the luxury of an idle afternoon in that day and age, then one would have been bourgeois and would have immediately alerted the local constabulary - for the Tosher’s domain was none other than the city sewers themselves, and entering them was as illegal as it was dangerous.

Because the fetid waste of the entire metropolis was flushed straight into the Thames, there were openings along the river bank which allowed access to the vast network of ancient excrement-encrusted catacombs. Dressed in velveteen coats and armed with nowt but a lantern and an 8-foot iron hoe, a party of courageous Toshers would thus embark on a perilous quest into the labyrinthine underworld in search of untold treasures, most of which consisted of bits of rope and the odd nail. Besides the risk of disease, noxious gases and general nausea produced by so much shit and piss, there were numerous other life-threatening dangers to be braved. Such as powerful sluice torrents, dodgy crumbling brickwork, cesspits that acted like quicksand, and rats the size of cats (and occasionally, cats the size of lost, bewildered and undernourished cats). Plus, they had to get out before the tide of the river rose and either blocked their exit, or drowned them in a rush of only-slightly-less-polluted river water.

There were also rumours of a ferocious tribe of feral pigs said to dwell beneath Hampstead Heath. The story goes that a severely unlucky pregnant sow somehow got washed into the sewers and proceeded to litter and rear her offspring, feeding them on the offal and garbage that came their way. Whether or not successive generations continued to procreate thus producing a hideous race of inbred hog afflicted with congenital deformities, is unknown. Whether or not they started wearing colour-coordinated ribbons, eating pizza and speaking in a language comprised of meaningless catch-phrases, is also sadly unknown. No Tosher would dare go near the area in case it was true. Mayhew certainly didn’t.